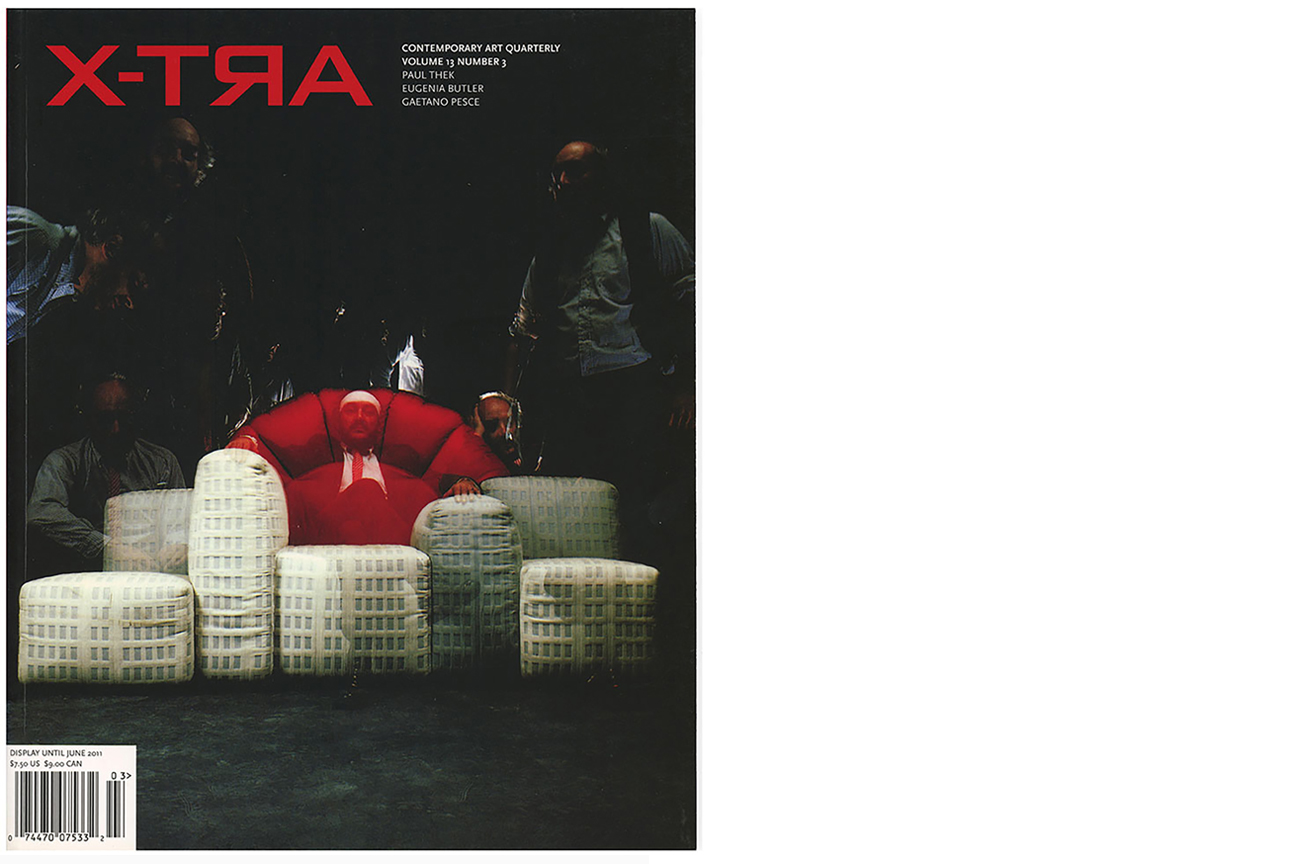

Gaetano Pesce and Aleatory Design

X-TRA Art Quarterly Spring 2011

Gaetano Pesce Tramonto a New York, 1980

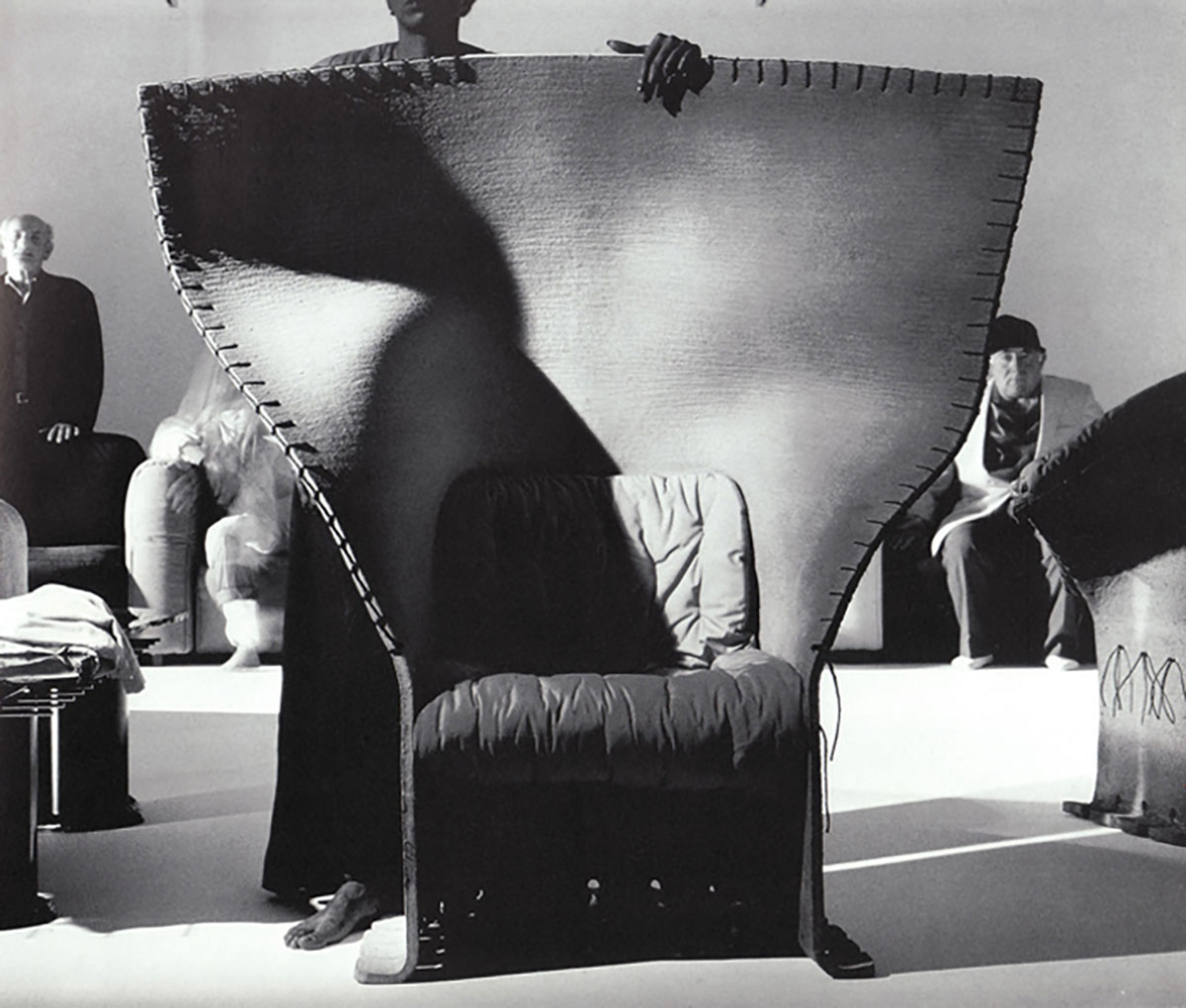

The landmark 1972 exhibition The New Domestic Landscape: Achievements and Problems of Italian Design looms large over contemporary industrial design history. The exhibition, at the Museum of Modern Art, showcased the work of young Italian designers such as Enzo Mari and Ettore Sottsass, as well as influential collaboratives including Superstudio and Archizoom. Like many so-called “landmark” exhibitions in other fields, The New Domestic Landscape included conspicuous oversights and sweeping generalizations, but in the most basic sense, the designers from this exhibition who still have cultural relevance now, often grouped under the vague rubric of “New Design,” each advanced strategies for dismantling the rigid structures and rules of modern functionalism. Mari’s text-based contribution to the show, for example, criticized industrial manufacturing by encouraging a return to language and the handmade, the early stages of Mari’s pedagogy of autoprogettazione. Sottsass’s Superboxes embraced decoration and destabilized the Miesian imperative of form following function, setting the stage for the influential group Memphis and the culture of postmodern design that came to define the 1980s. Superstudio and other less product-oriented collectives introduced the notion of a counterculture to the realm of industrial design by shifting emphasis out of object manufacturing and marketing and into a more theoretical realm. Gaetano Pesce (born 1939) was among the younger designers in The New Domestic Landscape, and he was the only one to be included in the “Design as Commentary” chapter of the catalog. “Design as Commentary” was situated awkwardly between the two larger parenthetical groupings, “Design as Postulation” and “Counter Design as Postulation,” which contained the other thirty-one designers in the show. The example of Pesce’s work featured the most prominently in the exhibition was the UP 5 chair (1969), better know as La Mama, a bulbous form made of bright red, expanded polyurethane that is packaged in a vacuum-envelope that compresses the chair to a tenth of its volume. The La Mama chair is presented as a political work—a feminist polemic on sexism and a commentary on the homogeneity, severity, and rigidity of an excessively masculine world. In a 2001 conversation with Peter Halley and Cory Reynolds in Index Magazine, Pesce describes the chair as “an actual representation of prejudice against women [who are] prisoners under the prejudice of man and the masculine world.” Over the course of his career, the chair has remained central to Pesce’s writing, which posits a more fluid creative mind in opposition to the dominant masculine structure of capitalism. Pesce explains, “Our education teaches us to only use one part of the brain, the masculine side. Society has always considered the masculine thinking style better than the feminine one, in work and in life… So now, if you express yourself with the feminine side, you will be very original. And you will be innovative…the ‘female’ brain is elastic. It is not rigid, not dogmatic, not totalitarian.” Gaetano Pesce Feltri Chair, 1987 The positioning of any industrial design practice as political, much less feminist, is inherently problematic. Of the thirty-two designers in The New Domestic Landscape, only one is a woman (Lucia Bartolini of the collective Archizoom). And although humor is an essential aspect of Pesce’s work, the La Mama chair runs the risk of being cartoonish. The notion that a busty piece of furniture is a vehicle for liberating women is at least as ridiculous as it is compelling. At the same time, industrial design, by definition, is categorically incapable of maintaining an oppositional relationship to the capitalist structure that supports it. Yet despite these apparent contradictions, Pesce returns to the unique potential design has—both in its idealized intellectual forum and its more compromised relationship to industrial manufacturing—to reach wide audiences, particularly in contrast to the more elitist and inflexible constructs of contemporary art and modern architecture. (Pesce facetiously describes the latter as “the queen of the arts.”) Pesce speaks frequently of Duchamp and Warhol, but dismisses contemporary art as exclusive and homogeneous. He criticizes museums for having less cultural relevance and regional authenticity than supermarkets and department stores. Allegedly, legendary art dealer Leo Castelli approached Pesce shortly after the opening of The New Domestic Landscape and told him he would like to work with him, but only on the condition that Pesce would agree to maintain a certain characteristic throughout his work for the remainder of his career. Pesce turned down the offer. Pesce’s work is most powerful not when it focuses on a broad political agenda, but rather when it reflects on the very processes and cultures that produce objects. First and foremost, Pesce’s cultural contribution is the showcasing of incoherence—a celebration of the flaws and imperfections that inevitably emerge within manufacturing processes. The implied critique of the de-humanizing landscape of mechanical production, the alienation of the workforce that produces it, and the growing disconnection between design and production is often more poignant than the pointed political motives of specific objects. Pesce tests the limitations of mass production by constantly exploring the potential for a unique object to be produced through the channels of industrial design. He labels his approach broadly with the neologism “aleatory design,” which is derived from the term “aleatoricism,” the use of chance in the production of art commonly associated with the Dada movement and French Surrealist writing. The results, more often than not, are series of objects that are industrially manufactured but retain unique characteristics; the human hand remains visible and the defect becomes a generator of content. In this sense, the central idea of incoherence becomes the unifying characteristic of Pesce’s work—a consistency based on inconsistency. Declarative slogans repeat in Pesce’s writing: “repetition destroys the minds of people,” “the future is feminine,” “routine is bad for the brain,” “freedom is incoherence.” This fascination with the flaw as the creative catalyst of aleatory design emerges as the through-line of Pesce’s forty-plus years of work and sets it apart from the standardization of conventional industrial design Gaetano Pesce Delila Chairs, 1980 This summer, the Italian Cultural Institute in Los Angeles hosted the first major exhibition of Pesce’s work on the West Coast. Gaetano Pesce: Pieces from a Larger Puzzle includes forty years of work, ranging from the UP series to several prototypes for a line of customizable plastic shoes currently in production for the Brazilian company Melissa. The exhibition was curated by Francesca Valente, the Institute’s director; John Geresi, a banker and a collector; and Peter Loughrey, the director of Los Angeles Modern Auctions. Los Angeles-based collectors Michael and Susan Rich, who are major patrons of Pesce’s work, loaned a conspicuous majority of the works on display. As the title suggests, the show focuses almost exclusively on prototypes and examples of commercially produced lines of furniture and objects. Despite what the press release implies, it is not so much a retrospective, because the visionary architecture, set design, and drawing that provide the foundation for Pesce’s better-known furniture are entirely absent. Nonetheless, it presents a compelling collection of Pesce’s work. The work in the main gallery is installed informally on wooden shipping palettes, an orange fiberglass ladder/shelf, and a plywood sawhorse table with an informal grace that feels indebted to one of Pesce’s closest associates and supporters, design retailer Murray Moss. A second gallery (in the institute’s library) includes a red and black 1 Feltri chair (1986) and several vitrines that hold books; handmade, plastic exhibition announcements; and a pair of remarkable, cast glass Cirva bowls (1992). Stacked on a pile of customized shipping palettes in the main gallery, the most compelling objects in the show—the Greene St. Chair prototype (1984) and accompanying wall drawing and the Golgotha Chair (1972)—have undeniable sculptural presence. The Golgotha chair—a simple sheet of fabric impregnated with fiberglass resin to take an approximate shape determined by its fabricator—was the first line of furniture Pesce produced in a diversified series and the example on view is a particularly elegant piece. Unfortunately absent is any record of the theatrical promotional photographs of these products in elaborate mise-en-scène, which perfectly capture Pesce’s simultaneous concern for history and his disregard of convention that underlie the more challenging aspects of his practice. The resistance to standardization in Pesce’s work defies the aesthetic expectations of even the most sophisticated buyer. Pesce articulates this as a distinction between his work and that of his Italian peers with whom he is so often associated. In a lecture in Los Angeles preceding the opening, he told an audience member: “Enzo Mari is a very great mind; when he talks it’s a different story,” and “Sottsass didn’t push design to limits that are unknown. He kept things in the decorative sense, and personally, I hate the decorative sense.” At the center of the crowded main gallery is a single Sansone Table (1980) (companion to the better-known Delila Chair [1980]), a thick resin table cast in a flexible mold that leaves the final shaping of its irregular top at the discretion of the fabricator producing it. The same worker determines the various colors of resin that are poured into the mold, such that no two pieces are exactly alike. Given how important the idea of the unique multiple is to Pesce’s work, it is unfortunate that the exhibition does not take the opportunity to show several iterations of the same piece in such a way that the variations in production would become visible. Multiple editions of the Sansone I table, in particular, would clearly articulate the substantial differences and uncanny similarities that arise in the production of Pesce’s diversified series. In the more recent line Nobody’s Perfect, represented most notably here by the bright red Nobody’s Chair (2002), fabricators are instructed to make alterations throughout the process of production, to never repeat a gesture. In the series of plastic bowls, bracelets, and vases that Pesce created for Fish Design, which are prominently featured in the exhibition, the inherent entropy of the sloppy extruded plastic guarantees inconsistency from piece to piece; incoherence is literally designed into the production of the work. If the idea of freedom through incoherence is the philosophical touchstone of this practice, a dedication to the evolving technology of plastics provides its material continuity. Much has been made of the fact that Pesce, like his teacher Carlo Scarpa, worked at several Murano glass factories (Moretti, Vistosi, and Venini) while in architecture school. The influence is evident in the Medusa vase and the Amazonia Mulitcolore vase, which emphasize the connection between his use of plastic and a long history of glass in the decorative arts (an antecedent, in so many ways, to the idea of a diversified series). These pieces suggest the extent to which the idea of aleatory design is predicated upon two essential prerequisites: an intimate relationship between designer and craftsman and the material properties of polyurethane resin. Though his studio is based in New York, Pesce’s work is still fabricated almost exclusively in Italy. The collaboration with manufacturers who are working to accommodate the interruptions and improvisations in the manufacturing process is essential to the production of this work. Equally essential are the physical characteristics of plastic resin—flexibility, lurid color, translucency, even its tensile strength and specific fluid dynamics. Pesce returns frequently to the example of an unbaked loaf of bread taking a predictable but unique shape in describing the conceptual advantages of cast plastics. Looking at a range of projects in a single gallery, the extent to which material, more than form, provides continuity in Pesce’s oeuvre becomes evident. At first, Pieces from a Larger Puzzle feels awkwardly positioned between a museum exhibition and a furniture showroom. More specifically, it raises the question of why Los Angeles, the capital of creative capitalism, is still so unsupportive of challenging postmodern design. The expansion of Moss, a store to whose identity Pesce has been inextricably attached for years, to Los Angeles was a commercial failure. And with the exception of the remarkable 2006 exhibition Ettore Sottsass: Designer at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, this era of design is largely unrepresented in the city that would seem for so many reasons to be its most logical proponent. Yet, in Pesce’s case, the consideration of the venue begs the question of a more appropriate context for a career predicated upon the dominance of the supermarket over the museum. Given the constraints, Pieces from a Larger Puzzle succeeds in its objective of introducing this iconoclastic practice to a broader audience on the West Coast. And even the restrained presentation of the work on view is more than enough to show how this dynamic approach to object making has resonance far beyond the narrow confines of industrial design.

X-TRA Magazine, (vol. 13, no. 4), Spring 2011

◼️